This insight is a case study produced by our partner Roberto Rittes, CEO of Nextel between 2017-20, in partnership with our Digital study group. Throughout the case, the factors that led to the successful transformation of Nextel, which culminated in its sale to Claro in 2019, are addressed.

Fight to Live Another Day

When I took over Nextel in April 2017, I had a single objective: not to let the company fail. Our shares, traded on the NASDAQ, had fallen 97% in just two years. The company, which had been a monopolist of an attractive and profitable niche, mobile radio service since the late 90s, saw the explosion of 3G/4G internet, smartphones and WhatsApp make it obsolete.

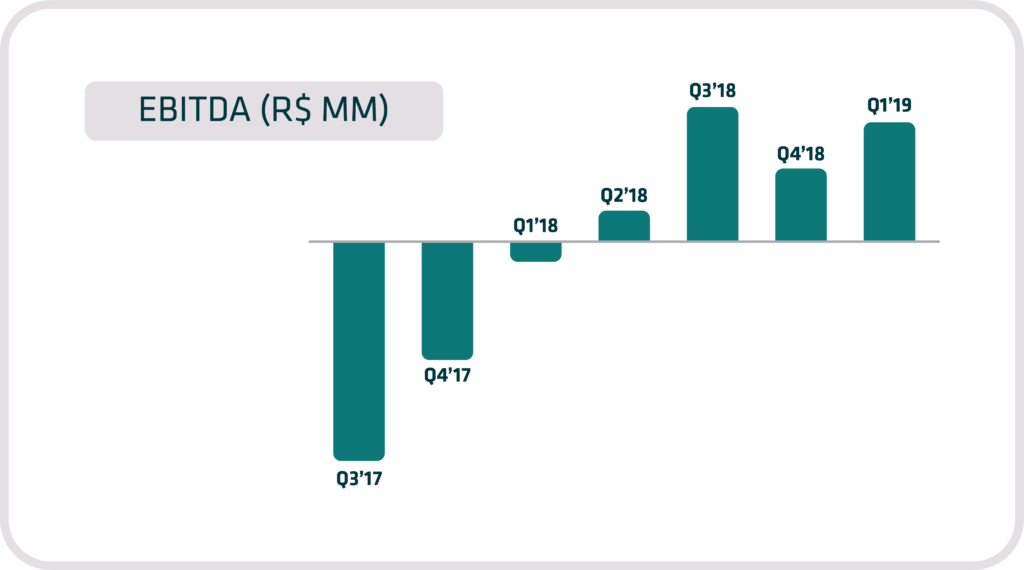

Already weakened, after its user base shrunk by more than 30% in 24 months, the company finally launched 3G services in São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro in 2014. Despite initial success in converting radio users in those regions to the new technology, when I arrived, the company's customer base had been stagnant for two years. And the great villain of this story was churn, which at the time was above 4% per month - that is, in 12 months the company lost more than 50% of the customers that had started the year. If the operational situation was complicated, the financial situation was even worse: very negative and worsening EBITDA, little cash and a large debt.

In this context, there was no time to waste and I set out for a quick diagnosis that culminated, 50 days after my arrival, with the launch of an ambitious package of efficiency initiatives to get the company out of the death spiral. Between mistakes and successes, we closed 2017 with very encouraging results: we reduced churn by 40%, more than doubled NPS and reduced the EBITDA hole.

The new, extremely simple family of plans was a hit with new and old customers. This allowed us to renegotiate the debt with the banks, giving us the impetus to embark on the complete transformation we envisioned. With a young, excited and empowered team, we were very excited about the opportunity to do something great. The results achieved in just over six months showed us that it was possible to turn the steering wheel, no matter how heavy it was.

Excitement aside, our reality was difficult and we didn't even have the investment power of the “big 4” (Vivo, Claro, TIM and Oi), so we would have to do it differently. To this end, we defined four pillars that would be our differentials: agility and internal climate, customer satisfaction, costs and innovation. To bring more clarity and pragmatism, we unfolded these pillars into 10 missions and thus our game-changing plan was born. Called Nextel 2.0, it was launched when Nextel was celebrating its 20th anniversary in Brazil and aimed to change the company by 2020. At least the numerology seemed to work.

Once the direction was set, it was time to make it happen. Obviously, a transformation of this nature is a major change management project, which in many ways is more complex than implementing specific efficiency actions, as had been the focus in 2017. The first step was obviously to “sell” the plan to the entire company and so we embarked on a roadshow where, over the course of presentations, we showed the vision of Nextel 2.0 in detail to the entire team.

To maintain engagement and alignment, we intensified face-to-face and virtual communication actions, including the relaunch of the corporate intranet using the Facebook Workplace platform, a corporate social network that, due to its familiar format and orientation to videos, played a central role in our daily lives. Most importantly, we encouraged two-way dialogue and began to use slido.com at all our meetings, a platform that allowed anyone in the organization to ask questions, often harsh and anonymous, but which were always answered in an objective and transparent manner. Finally, this two-way and transparent communication model was something that lasted throughout the cycle.

KPRs: our transformation paradigm

To put our vision into practice, we knew that we would have to change the way the company operated. And the truth is that at the beginning we had little idea of how the new model should actually work. Both I and most of the senior team had a DNA of efficiency inspired by the management model and culture that Ambev and then 3G spread around the world. Nextel still had traits of the rich American multinational that it was in the not-so-distant past, and this culture of efficiency would be fundamental to help us close the cost drain. But we also knew that to make the Nextel 2.0 plan happen we would need to combine this model with the new economy.

In this territory, we obviously had the references that all companies have - the Spotifys, Googles and Amazons of life, companies that we admired and that had managed to create agile management models as we wanted, but which were already born digital. Transforming a 20-year-old American multinational into a mix of Ambev and a new economy would require something different and very specific. The most interesting thing is that all these references to the new economy had only one thing in common: each one had discovered the model that made the most sense for their own reality. We knew that we had to do the same and walk our own path. For this, we would need good people to challenge us, add knowledge and help us to give rhythm and cadence to the execution of the transformation. We brought in market experts for specific topics, and Visagio to help orchestrate and play on several fronts. With this help, we began to create our new people and management model.

The first hurdle in implementing it was the plan itself. We knew where we wanted to go, but we intentionally had no idea how to get there. I've always been critical of the energy wasted building transformational roadmaps. In our case, a nervous turnaround, it would be crazy to spend time on a futurology exercise that after a few months would certainly become another work of fiction in the Nextel archives.

The destination was clear, but the path would be defined step by step. At the time, Nextel Brasil was an American corporation listed on the NASDAQ, so we reported to the board of directors in the United States. In it, our main rite was the validation of the three-year business plan and the annual budget, which were a translation in large numbers of what we expected to achieve with the ambitious transformation plan. This process resulted in aggressive targets - not only for revenue, EBITDA, and cash flow, but also for the NPS, given our pillar of being the telco most admired by clients. In addition, these targets were the basis of our guidance for the stock market, but the good news is that they were only a guide, setting the limits and quantifying the expected impact of our actions, but we were completely free to manage what was necessary.

With all this pressure to improve results, we knew that the transformation would need to be accelerated and we would have to show evolution with each cycle. Therefore, we decided to abandon the traditional annual cycles, and from then on all planning at Nextel would be quarterly. This brought us the challenge of mobilizing the entire company every quarter to define and execute the new initiatives that would bring us closer to the vision of Nextel 2.0, and that's when we decided to dive headlong into the OKRs (objectives and key results) to ensure alignment, focus, and rhythm.

Talking about OKRs today is raining in the wet and if you don't know the methodology, you may worry. At that time, we already knew or thought we knew. The concept of OKRs is extremely simple: basically an inspirational phrase to define the objective, combining clear criteria for measuring its achievement.

Purists will certainly be mad, but among us, OKRs is an improved version of the traditional project management models that we've all used for decades. The main difference is that, in the best agile spirit, OKRs focus on what you want to achieve and not on how it will be done. In the traditional model, it is very common for teams to become hostages of defined activities and schedules when very little is known about the problem/opportunity, while in the OKRs model, teams have the freedom and autonomy to define their paths and change planning if they deem it necessary to achieve the real defined business objectives.

The shorter planning cycles of the OKRs force teams to break large problems into workable pieces in a quarter, generating pragmatism and focus on deliveries, while long traditional projects are black boxes with difficult to measure results, especially in the early stages. Thus, the OKRs gave us the flexibility to reevaluate initiatives every quarter, allowing us to abandon those that had already achieved satisfactory results or those that had failed to prove their merit. In the traditional model, we would most likely follow the schedule to the end in a dogmatic manner.

Although the concept is simple to understand, implementing OKRs is very difficult and most of the companies we visited at the time, even in the new economy, were still fighting their heads. And the problem was that, precisely because of its simplicity, the concept is very unprescriptive and when implemented it raises several doubts:

- What is the granularity of the OKRs? Board of directors? Time? Project? Individual?

- How do you cascade the OKRs between these various levels?

- If the same person is in more than one team (e.g., area and project), does the team have more than one set of OKRs?

- How to implement the concept of the “stretched rope”, which is neither intuitive nor objective? The methodology assumes bold goals and defines success as any achievement above 70%, which I internally called “70% is the new 100%”. But unfortunately our brains are conditioned that success is to exceed 100% and we have difficulty defining goals that we don't believe can be fully achieved. In practice, it becomes confusing, since some teams incorporate the concept of the tightened rope while the majority, at least at the beginning, are stuck with the traditional model. How to ensure accountability in this scenario?

- Methodological purists strongly discourage the association of OKRs with compensation, but how could we guarantee the necessary attention to the topic and implement the meritocratic culture we wanted if we didn't link this topic to compensation?

- What to do with KPIs, which until then were the epicenter of our management model?

Today we were able to find the answers to most of these questions, but at the time we had to experiment to learn. Thus, we did what until then had been the largest implementation of OKRs in Brazil. After a pilot on a board for a quarter, at the beginning of 2018, we added another 1,500 employees to work with OKRs.

Little did we know that, in addition to these conceptual doubts, we would literally be buried by exceptions and unforeseen operational issues. During the year, each quarter, we were forced to make numerous adjustments to operational and conceptual issues in the model and, however necessary, we received a lot of criticism from the team for the constant changes.

Despite all the improvements throughout the year, we ended 2018 with the feeling that something more structural was still missing than the adjustments we had made throughout the year. And what made us clear about what was missing was the great success of the management model in 2018: Corporate OKRs, which were the main initiatives, usually around 12, that we chose to mobilize the company each quarter. If we were able to replicate the success in performing the great long-tail songs, we would create dozens of small transformations scattered around the company and then things would be cool.

The secret behind the success of corporate OKRs

In practice, corporate OKRs were the focus of all leadership, but the main actors were inevitably the business (commercial, marketing, and service) and technology areas. Then we realized the main elements of the success of corporate OKRs: quality discussion to build a shared vision, breaking down major challenges into steps that would fit in a quarter, and clarity of where we needed to go and where we should act.

The corporate OKRs cycle began with a workshop in the last fortnight of the current quarter. There, where the company's extended leadership, around 30 people, met for approximately five hours in our auditorium and inevitably ended with a list of approximately 12 initiatives (corporate objectives) that would be the company's focus in the following quarter. Ten days later, we had a second meeting where the owner of each corporate objective, most of the time an accelerated manager and doer, presented for discussion and validation the direction, team and expected impact (key results). Due to its construction model, corporate objectives have always had a lot of legitimacy and buy-in. Additionally, in the workshops with the leadership, we had moderators who helped us get out of the pillars and KPIs and arrive at objectives that would fit within a quarter. The discussions were heated, but it worked really well.

With the corporate OKRs defined, we began to align the OKRs of the rest of the company and even areas directly involved in the corporate objectives needed to challenge other aspects of their operations by defining what we called 'Area Objectives'. Unfortunately, the vast majority of areas did not dedicate the necessary time or did not perform this rite properly. In many cases, OKRs were produced at the cash register by the area leader, without the team's involvement, or even when working as a group, they were lost in this process of “peeling the onion” and defining initiatives that would fit in a quarter. In the second half of 2018, we introduced OKR Week, which always took place in the first week of the new quarter. During that week, the areas could, if they deem it necessary, schedule sessions with facilitators who helped the teams define the OKRs.

The model was working well for the teams that made use of those sessions. Thus, in 2019, we significantly increased the resources available during OKR week and made these sessions mandatory for all teams. This support, combined with the pressure of the management team's participation in the area meetings, provided the necessary push to remove most of the teams from inertia.

These operational changes were important and helped a lot, but we knew that we would need to touch on a central point of the concept of our model to really accelerate the area's OKRs: to bring the KPIs back. At the beginning of the implementation of the OKRs, we thought that the KPIs would hinder the roll-out and we decided to leave their management solely to the areas, without the monitoring of the transformation team. However, without the charge, in a short time we noticed that many areas abandoned the KPIs.

In corporate OKRs, we always started from the 4 pillars of our transformation and the KPIs of our budget to end the workshop with a list of 10 to 12 objectives to deliver our results. In the process of planning the areas, these starting points were not so clear. To make matters worse, in some cases KPIs began to appear disguised as OKRs, especially in the commercial and operations area. It was clear that OKRs had not come to replace KPIs, but to add to KPIs. We realized at that time that KPIs and OKRs were not conflicting, on the contrary, they were two sides of the same coin.

KPIs, as their name says, are the main business metrics, encompassing the various relevant dimensions, often inspired by the Balanced Scorecard. They work well as performance measurement, but they don't solve the problem of making things happen and, even so, are often associated with reactive PDCA cycles that dispose dozens or hundreds of initiatives to a project office. In our model, the OKRs took on the role of organizing and materializing the KPI improvement agenda, which in other words, implies that they were the starting point for the OKRs. In the fan-obsessed world we live in, OKRs are “sold” with the model to replace KPIs. We embarked on this hurdle, but thankfully we changed course quickly.

Thus, already at the beginning of 2019, we started with the model that integrated KPIs and OKRs. In an attempt to organize concepts and this alphabet soup, the term KPR was born, which not only shows the interrelation of the two concepts, but mainly makes clear the focus on results. Indicators look back and are only a means of measuring performance. What really matters is proactively building results.

In the new model, each area had between 3 and 5 KPIs, no more than that, that measured the contribution of the area to the business. Unlike corporate OKRs, KPIs and area OKRs were not monitored by the executive committee, but were governed by the area's own governance with me and the Chief Transformation Officer.

Key learnings

The implementation of this model was far from perfect or without hiccups, but it managed to structurally change a 20-year-old company. Both the management model and the Nextel 2.0 plan achieved the Hearts and Minds of almost 3,000 people and thus made it possible to implement an ambitious transformation that quickly generated a high impact on the business. We had a lot of external help, especially from operational consultancies, especially Visagio, and almost two dozen advisors, usually former executives who supported us in the transformation of specific topics.

However, the most interesting thing is that the vast majority of the protagonists of this transformation were at Nextel when I arrived. The company had a strong team that was being plastered by a heavy structure at the top and many hierarchical levels. But those talents were only able to emerge thanks to the 30% reduction in headcount, which eliminated almost two hierarchical levels in the company average.

On the same day that I took over the company, I eliminated the three most senior positions in the company. Beyond space, this exchange of leadership breaks the link with the past and creates much more fertile ground for transformation. Our driver in reducing the structure was to save money, but today I am clear about the importance of breaking with the past and empowering new blood, but that can also be from within the organization.

Despite the difficult path to reach the KPRs, the management model was one of the protagonists of this transformation. In the first year, we changed our approach every quarter, and then we stabilized. We even did individual OKRs at the beginning, but it took a lot of time and the OKRs came out with poor quality given the team's maturity in the concept, so we abandoned it. By the way, the humility to recognize mistakes and go back was fundamental throughout the process in various situations.

The topic of performance evaluation is one of the things that I don't believe we have solved 100%. I, at least, experienced a constant conflict between my more historical meritocratic vein and a more collaborative approach, without individual goals and much more focused on the performance of the company and the teams, as the “digital thinkers” recommend. We ended up doing something hybrid, with a higher percentage for the company's goals and a lower percentage divided between behavioral assessment (ten criteria, eight of which are company standards and two flexible by area) and a discretionary assessment by the manager of the individual impact of people in achieving results both in everyday life and in transformation, with a forced curve.

In addition, we placed a very low percentage linked to the achievement of the teams' KPIs and OKRs, basically to highlight their importance for the company (despite the express recommendation of the “OKristas” not to link OKRs to the assessment, which we understand but decided to subvert a bit). The model worked, but it had its limitations. For example, the teams from the areas that were assigned to the squads had very little interaction with their functional managers in practice, but they continued to be evaluated by them. Anyway, we had issues that were not yet fully resolved.

One of the most important points to highlight is the role of the Chief Transformation Officer in this entire process. We had the right guy (André Fossa), with experience both in consulting and large companies and in the startup environment. Thus, he had good relations with the executives and knew when to harden the discussion, while he was also respected and spoke the language of “digital kids”. His area managed the entire transformation program, including routines for planning and reviewing KPIs and OKRs (area and corporate), mediating conflicts between areas, etc.

Unlike what we did at Nextel, where we implemented OKRs across the company all at once, today I'm clear that the OKRs journey must start at the top of the company and then cascade down. In addition to being easier and less risky, the bulk of the impact comes from corporate objectives. And modesty aside, we've created an excellent template to execute that agenda.

Our intensity of communication and focus on corporate objectives generated very high alignment and mobilization of the entire company. Even the normally difficult task of gathering resources from different areas to assemble the team responsible for the corporate objective was relatively easy. As corporate objectives had priority in the company and had high visibility with the leadership, and were monitored monthly by the executive committee, people liked to be part of the teams. These multidepartmental teams focused on corporate objectives weren't agile product teams. Strictu Sensu Given that the people were not 100% dedicated and the teams themselves were not perennial. That same partial dedication of these “false squads” (30% to 50%) resulted in more senior teams that worked very well for the complex and high-risk problems that we had on our agenda.

Our Digital area had squads (in fact) that were responsible for supporting corporate objectives related to the development of products and solutions. Remember that we defined the objectives and key results, not how to implement them - this was defined by the teams themselves, who often used agile methods. In addition to empowering and encouraging teams' creativity, the model guaranteed rhythm and dynamism.

With this model, we translated our 3-year BP into an annual budget, the latter into quarterly KPIs and OKRs, which were divided into quarterly corporate objectives that were then broken down into smaller sprints through the owners and teams. With this, we guaranteed that our daily execution was fully aimed at what we had in the medium-long term (remembering that the vision itself, represented here by BP, was adjusting as we progressed). At the end of each quarterly cycle, we held a closing meeting where the teams presented the results, discussed and documented the lessons learned.

Results

The transformation that the team achieved in three years was incredible. We went from very negative EBITDA to positive EBITDA in just 4 quarters, and then on for all of the following quarters. In 2019, our positive EBITDA enabled operating cash flow to be positive despite the high capex characteristic of our industry. From stagnating in the number of customers, we were the mobile company with the highest growth rate in 2018. Our NPS came out of 14 and was always above 30 points, the best among the telcos, which led us to win the Anatel title in 2019 as the best operator in Brazil that year. And we went from a rate of 40% of dissatisfied employees to 5%. We stopped being a practically bankrupt company and became competitive again, which culminated in the purchase of the company by Claro for an unthinkable valuation before the start of the turnaround.

I purposely avoided talking about digital transformation and technology throughout this article, although that's what the market calls what we did at Nextel. I think that the transformation was very digital - especially in relation to the team's mindset. In the end, we had more agility and experimentation with the team being free to make mistakes, actual customer centricity (we implemented a Customer Experience program that was one of the pillars of growth and increase in NPS), agile product teams, etc.

However, I think the transformation went beyond digital. We had a very strong efficiency agenda, especially at the beginning, to turn off the faucet and guarantee minimum financial health to start dreaming of something bigger. And this agenda, unlike the digital transformation, which is exciting and generates positive energy, is quite tough. It involves layoffs, cost cuts, renegotiation of debts with banks, etc. Merging the two themes played an important role in ensuring that the team envisioned a better Nextel in the near future, which meant that we retained most of the talent.

This broader transformation approach (efficiency and digital/growth) is not exclusive to Nextel — there are even several books on the subject. We call it full transformation, but I've seen dual transformation, fit to growth, etc. I think the name is less important than the concept behind it and the way of doing it. I tried here to cover some of what we did, it may generate some insights, but I think that the most important thing is for each company to find its own path depending on the company's culture and moment. The most important thing is to get started — in our case this initial step was due to a near-death experience, but maybe that doesn't have to be your case.